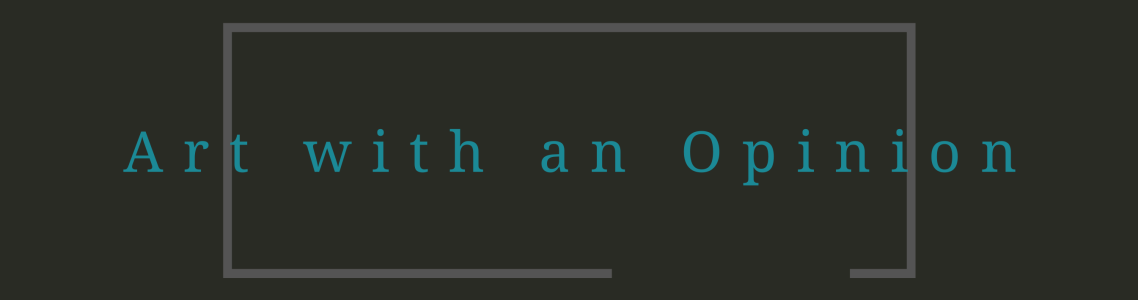

Tucked in a small corner at the far edge of the “Arts of Africa” exhibition at the Denver Art Museum, visitors will find a four foot by six foot acrylic on canvas created by Nigerian painter Moyo Ogundipe in 1997 (Fig. 1). Vibrant colors flow across the canvas, almost as if they are dancing, broken only by scattered figures in each third of the composition. Commanding the center of the canvas and the attention of the surrounding figures is a woman painted in dark green, her hand outstretched and holding a bird that gazes back and her. Above her head flies another bird of similar size and shape to the one in her hand. To the right of the woman sits a man on a horse; the horse and the man are disproportionate both to each other and the woman, and the man’s head is disproportionate to his body. On the left third of the canvas, almost hidden in the background, is a smaller kneeling woman holding another bird, facing a peacock and a snake. In the bottom left corner, Ogundipe hints at another figure, but it loses its definition in the background. No interpretive label is provided, just the basics of the artist’s name, title, and medium. These figures are unquestionably African, given the darker color of the central woman’s body and the shape of the man atop his horse, and the context of the painting’s location alongside other African art objects of similar shapes and styles reinforces this. But the piece is also markedly different from the rest of the objects in the gallery, both in its color and its medium, so even in its unassuming location within the exhibition, it still stands out.

The subject matter of Ogundipe’s Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions is solidly rooted in Yoruba mythological culture and artistic tradition, but the painting’s creation transcends its Nigerian roots. Ogundipe was an expat who fled Nigeria’s dictatorship for the United States in 1994, and he lived in various states during his 15-year tenure in America before returning to Nigeria in 2008 (Sytsma 54). Growing up, his father taught at Christ’s School in his hometown of Ado-Ekiti, where Ogundipe was introduced to the Western art practices that formed the foundation of his artistic pursuits as he continued on through university (Sytsma 50, 52). His artistic style and themes evolved over time, but Soliloquy was painted early in his self-imposed exile to the United States, and it reflects Ogundipe’s mindset at a specific point in time as he psychologically navigated the tumultuous history of Nigeria while living in America. The result is a colorful painting bursting with cosmological symbolism and nostalgia, offering an example of an idealized Nigerian mythos that captures the “lost glory of Africa” and serves as a distraction from the violent history taking place within Ogundipe’s home country (Sytsma 58).

Examining the mythology associated with each figure in Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions helps orient the painting within its Yoruba heritage. Ohioma Pogoson and A.O. Akande suggest the female in the center (Fig. 2) is a symbol of “fertility and growth,” honoring the “fecundity of women as mothers,” as she is rendered in a deep emerald green, a color often associated with fertility and life (Akande 12). This is further supported by the woman’s neatly plaited hair; in Yoruba culture, “a woman’s hair is believed to reflect her state of mind or important phases in her life,” and her tidy braids place her in her youthful, child-bearing years (Akande 12). Her hand holds a bird, which is a “[reference] to the mystical power of women, known affectionately as awon iya wa (“our mothers”),” which points to the woman as a powerful creator of life (Drewal 38). Above the woman’s head, a bird nearly identical to the one in her hand surveys the scene; this may be a reference to popular twin iconography in Yoruba culture. Ogundipe himself has also cited the birds as “[symbols] for freedom, for flying, for power, for majesty” (“Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions.”).

The equestrian situated to the right of the woman is another common motif in Yoruba art (Fig. 3). Two important symbolic themes emerge in this figure; first, the equestrian is viewed as a powerful warrior in Yoruba culture, and he is often “associated with Oranmiyan, the mythical founder of Benin and Yoruba dynasties” (Akande 13). The shape of this figure directly calls to mind traditional Yoruba sculptures, usually made of either wood or ceramic, that are often used in ritual ceremonies and other spiritual contexts. Second, the equestrian’s disproportionately large head in comparison to his body and his horse references ori, the head, which is thought to be “the site of a person’s essential nature,” as their “spiritual essence is sited in the inner head, (ori inu)” (Drewal 26). An enlarged head in Yoruba art is also said to “[convey] a person’s dignity and pride in positive achievement” (Drewal 26). The cone-shaped headdress atop the equestrian’s head, which contains a smaller image of the equestrian and his horse, references a Yorubaland creation myth, where “a creature descends and spreads earth on the surface of water to create a cone of land. . .This cone is a primal image for ase in the world” (Drewal 32). Ase is interpreted as life force, which in turn means that “[t]heoretically, every individual possesses a unique blend of performative power and knowledge—the potential for certain achievements” (Drewal 16). That the equestrian’s ase contains a smaller image of himself riding his horse suggests that the figure is focused on fulfilling his personal potential for achievement.

The smaller figures and the ubiquitous etched patterns within the composition also symbolize various Yoruba mythological themes and rituals (Fig. 4). The kneeling woman holding the bird to the left of the central woman is a direct reference to the same creation myth as the equestrian, but from a slightly different perspective, where a “divinity descended [to the earth] on an iron chain, taking along a snail shell (or gourd) filled with earth, a cockerel (or five-toed chicken/bird), and a chameleon. Upon arrival, the deity poured the earth from the shell onto the water, and the bird spread it to create land” (Drewal 45). Known as “Olumeye (One who knows respect),” the kneeling woman seems to be offering this cockerel in a ritual act of supplication, but it is unclear who specifically she is offering it to (Akande 14). According to Pogoson and Akande, “carved wooden bowls portraying female figures holding chickens are traditionally offered to guests as a gesture of hospitality and generosity,” perhaps suggesting the offer is to the central female figure, who could be of celestial or mythological origin (Akande 14). Adjacent to the kneeling woman sits a peacock, who is “a sacred bird and is considered to be the messenger between the people of Africa and the supreme god Olodumare” (“Bird of The Gods”). The snake above the kneeling woman’s head “[provides] a powerful metaphor for regeneration, since a snake regularly sheds its skin” (Sytsma 60). Both the background and all figures in the composition wear beautiful, flowing geometric patterns that lend texture and movement to the painting; these patterns may be an homage to scarification, a common ritual practice in various African cultures (Akande 12).

However, simply examining the Yoruba symbolism within the painting does not provide the full context for the piece. Ogundipe painted Soliloquy three years after he left Nigeria for America amidst widespread violence and military law in his home country. The unstable economic and political climate made it difficult for Ogundipe to pursue a career as an artist in Nigeria, and as the country’s infrastructure wavered and ethnic tensions escalated, he began questioning the nationalism and pride he felt as a Nigerian man through his childhood and young adulthood (Sytsma 53). His paintings during his early exile “gave rise to broader metaphysical questions related to the nature of existence and the universe,” and he looked to traditional Yoruba iconography for resolutions (Sytsma 55). Although Ogundipe did not grow up with a strong understanding of Yoruba traditions, as he was raised in the Western context of a Christian secondary school in Nigeria, he “made up for that deficiency later in life when [he] went back and really studied Yoruba art” (“Moyo Ogundipe Interview”). Many of Ogundipe’s works from this period reference universal creation myths, reflecting “a deliberate engagement with Yoruba art and philosophy along with a deeper understanding of their correlations with broader contemporary global art discourse” (Sytsma 53). Ogundipe brings these historic iconographies into a modern artistic dialogue by painting his compositions, which is a largely Western art practice, rather than sculpting or carving them as is traditional in Yoruba culture.

Ogundipe also avoids creating distinct storylines with his artworks; rather, each figure “[functions] autonomously as [an] independent [actor] on the mythic stage,” which gives “each character…the capacity to invoke multiple myths” (Sytsma 58-59). This allows the visitor to create their own interpretation of the work, whether from a Nigerian background or not, making his art more universally accessible to a wider audience. Without being tied to a cohesive narrative within his works, Ogundipe freely combined mythologies in his paintings to evoke a utopian idea of Nigeria, one which recaptures “the lost glory of Africa” and “[imparts] a peace and tranquility that belies most lived experience” (Sytsma 58). Janine Sytsma refers to this as “mythic revision,” where “the essence of the archaic myth is carried into the present, where it is offered as a new possible paradigm for society” (Sytsma 58). Ogundipe sought to remind his audience (and perhaps himself) of Nigeria’s ase, which had been lost amidst the tension within the country, but was still available and accessible if society recalled its origins.

By bringing these myths most commonly tied to ritual acts of performance with sculpted and carved characters into a two-dimensional painted space, Ogundipe updated these stories to make them more relevant for modern-day audiences. Sytsma interestingly notes that “Ogundipe [had] no intention of ritually activating the powers” of these characters, but he instead asks his audience to contemplate their existence and their meaning in a modern society (Sytsma 57). This makes his work distinct from the works of his predecessors, as much African art was created for ritual purposes, meant to be used and activated in ceremonies and other acts. Unlike the traditional arts of Africa, a painting cannot be worn like a woven cloth, it cannot be held like a wood carving, and it cannot possess its performer like a mask. A painting is static (though Ogundipe’s paintings are very much dynamic in their compositions), and thus can only be observed, thereby not directly engaging with the characters it depicts. Through this approach, Ogundipe impels the viewer to reflect on his choice of subjects and decide for themselves how they can be activated outside the four edges of his canvas.

Ogundipe himself has supported this open-ended interpretation of his works; in an interview with the Denver Art Museum (DAM), he stated, “It is futile to classify me as a Yoruba, African, or Nigerian artist. I am a human being…I am striving to produce an art that is a genuine reflection of me, as well as a universal statement” (“Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions”). Ogundipe successfully blends his Nigerian heritage with his Western-focused upbringing and his time spent abroad in America, where he first fully focused on his art career (Sytsma 54). It is perhaps this Western art influence that inspired Ogundipe to focus on aesthetics over function in his artworks; while he acknowledged that “there are certain things that influence [him], and those things have to show in [his] work,” he also emphasized that he wanted to “capture the shared decorativeness of life, the shared beauty of life” (“Moyo Ogundipe Interview”). His vibrant, dynamic paintings, especially Soliloquy, offer so much detail to observe, celebrate, and admire, and even without understanding the cosmological, mythological symbolism behind the work, it is still easy to appreciate its artistic beauty.

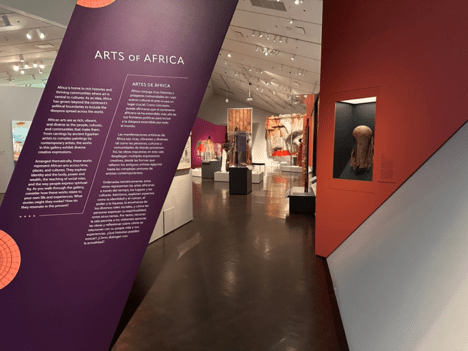

DAM contextualizes Soliloquy among its African art holdings, placing it opposite traditional wood carvings and other historical sculptures and masks from various countries, used for various purposes, without sequencing Ogundipe’s piece in any chronological setting. According to the exhibition text, DAM has arranged the gallery by theme, with works “[representing] African arts across time, places, and cultures,” and they work to tie these themes to the current moment by inviting visitors to “consider how these works relate to [their] own life and experience” (Exhibition Text). Soliloquy’s location in the gallery risks visitors missing it entirely as they walk through the exhibition, as it hangs on a far wall next to a very small secondary entrance/exit that looks as though it is a dead end. Even from a vantage point outside the exhibition’s secondary accessway, the painting is obscured by an angular wall with exhibition text orienting visitors to the gallery (Fig. 5). The piece itself is not accompanied by any interpretive wall text, leaving the visitor to create their own understanding of the work. On the opposite end of the gallery, visitors encounter a blend of DAM’s contemporary African art holdings and traditional African objects, with an El Anatsui sculpture and a Yoruban masquerade outfit anchoring the exhibition, both directly visible from the main gallery entrance. Throughout the gallery, the museum again connects the works to the current moment by playing an Afrobeats playlist, presenting “a style [of music] that emerged in West Africa and the UK in the early 2000s…that celebrates transnational Black culture” as a contemporary audio backdrop for engaging with the art (Afrobeats Wall Text).

DAM’s approach in this gallery both helps and hinders the creation of meaning in this particular painting; with influences as far-reaching as Ogundipe’s, Soliloquy would fit easily as well within its current home next to traditional woodworks, or among its contemporary companions on the other side of the gallery. By placing it alongside other African art objects from various time periods, DAM positions Ogundipe’s work specifically within its African cultural heritage, and the absence of interpretive wall text means no additional information is offered for anyone who may be curious about its unique medium of paint in comparison to the more natural materials found in the rest of the gallery. This approach negates the Western influences that inspired Ogundipe’s work and his techniques, favoring instead the Yoruba narratives that factored little into Ogundipe’s life until later in his adulthood. However, hanging the painting at an outer edge of the gallery does hint at meaning beyond its African roots; since it is located at an entrance/exit point, its position can be interpreted as either a gateway from the Western world into the African world, or as a transition from the African world into other realms.

The inclusion of audio art in the form of the Afrobeats playlist that accompanies the exhibition helps bring all artworks in this gallery into the contemporary sphere, as does the inclusion of visual recordings of various African performances that accompany the ritual objects surrounding Ogundipe’s piece. From this perspective, DAM does an excellent job of reminding its audience that African art is not a bygone practice, but something that is still relevant, useful, and widely practiced in today’s world. This narrative fits nicely with Ogundipe’s painting, as he invites his audience to contemplate how they can adapt these traditional Yoruba mythologies to their present-day experience. Ogundipe’s open-ended presentation of important characters in these myths, along with his painting them in a manner that honors their sculptural counterparts, puts them in flexible dialogue with the neighboring objects, allowing the painting to reinforce the meaning and contemporary uses of those ceremonial objects, and the objects to affect the meaning of the painting.

However, Soliloquy is a global object. Its influences draw from Ogundipe’s time in America and upbringing in Western-style schools in Nigeria, and the painting would also align with an exhibition focused on cross-cultural objects. Ogundipe’s desire to paint pieces that reflect universal sentiments that can be appreciated by anyone from any culture is important to consider, and placing it in a solely African exhibition neglects that additional layer of meaning. Instead, it would be beneficial to situate Soliloquy in an exhibition that accommodates these narratives, with interpretive text accompanying the piece to help audiences understand its significance from a diasporic perspective that relies heavily on Western techniques. This piece would also be at home in an exhibition exploring the transformation of cities, countries, and cultures over time, as a sort of documentation on what customs have been lost to time and which still hold strong in contemporary society, and how artists work to recover, share, and expand those lost customs. This approach would honor Ogundipe’s nostalgia for his country’s traditions while still inviting audiences to consider the contemporary impact these traditions could inspire. Lastly, this painting could also serve as an anchor for an exhibition exploring the impact of Western art on African art, and how new mediums introduced to Africa through colonialism and beyond expanded African art repertoires.

Ogundipe has also stated that he is “just the medium…the hand…the laborer that brings these things into being” (“Moyo Ogundipe Interview”). As he created his paintings, he stepped outside his mind and let instinct take over; rather than concern himself with a specific end product, he simply “[looked] at the nearest color next to [him]” and put brush to canvas (“Moyo Ogundipe Interview”). This approach invokes a certain mysticism in the creation process, turning it into its own type of ritual performance. In this interpretation, Ogundipe’s painting becomes a ritual object like those presented in the cases opposite the painting in the gallery—the artist is the diviner, and the painting is the means of divination, connecting both the artist and the viewer with the spiritual beings depicted on the canvas and lending the painting its own sense of agency. From this perspective, the painting’s location within DAM’s “Arts of Africa” gallery is perfectly apt, as the focus shifts from the medium to the message, and importance is placed more on the object’s ceremonial purpose than the influences on its physical creation.

It is interesting to note that Ogundipe’s tenure in Denver, Colorado was his last stop in America before returning to Nigeria; he served as the Denver Art Museum’s artist-in-residence for a year and taught at the University of Colorado at Denver during his time in the city (Sytsma 60-61). While the DAM website contains various perfunctory analyses of Ogundipe and his paintings, Moyo Okediji, a former curator of African and Oceanic arts at DAM, expressed that Ogundipe’s “‘work was treated with romantic condescension by the press’ in Denver,” which could have contributed to how Soliloquy is interpreted and presented within DAM (Sytsma 60). If critics and potentially curators view this work as a static African object, rather than a dynamic, contemporary revision of mythmaking that extends beyond its African heritage, it runs the risk of inadvertently being “typecast” as a solely African object, thereby neglecting its global significance in the museum sphere.

Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions stands open to multiple interpretations, offering curators and visitors countless ways to understand the painting. Given that the primary subject matter of the piece concerns Yoruba creation myths, the Denver Art Museum’s placement of the piece in its “Arts of Africa” exhibition suits the primary interpretation of the piece, and its location within the gallery inspires dialogue both with its surrounding objects and its visitors. When Ogundipe painted the work, he was internally grappling with widespread unrest in his home country of Nigeria, and exploring these Yoruban creation myths provided solace and comfort, along with the hope that Nigerian society would once again thrive and regain its lost glory if it gained wisdom and guidance from these origin stories. However, viewing this piece solely through the lens of its Africanness ignores crucial influences in Ogundipe’s artistic career; namely, his upbringing in Western-style schools and early introduction to Western artworks that inspired his own practice. It also sidelines Ogundipe’s personal perspective on creating art, in which he is simply an intermediary for his connection to his subconscious and the divine. Finally, it neglects the status of the painting as a global object, not tied specifically to any one location, but serving as a vessel for both Western and African meanings.

Appendix

Fig. 1: Ogundipe, Moyo. Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions. 1997. Acrylic on canvas. In exhibition “Arts of Africa” at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Seen on 5 Oct 2024. Photo taken by Tanya Yorks.

Fig. 2: Detail: Ogundipe, Moyo. Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions. 1997. Acrylic on canvas. In exhibition “Arts of Africa” at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Seen on 5 Oct 2024. Photo taken by Tanya Yorks.

Fig. 3: Detail: Ogundipe, Moyo. Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions. 1997. Acrylic on canvas. In exhibition “Arts of Africa” at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Seen on 5 Oct 2024. Photo taken by Tanya Yorks.

Fig. 4: Detail: Ogundipe, Moyo. Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions. 1997. Acrylic on canvas. In exhibition “Arts of Africa” at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Seen on 5 Oct 2024. Photo taken by Tanya Yorks.

Fig. 5: Secondary entrance to “Arts of Africa” exhibition at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Ogundipe’s painting is directly opposite the object along the red wall seen on the right of the photograph, obscured by the gallery’s secondary entrance. Photo taken by Tanya Yorks.

Works Cited

Scholarly Sources

Akande, A.O. and O.I. Pogoson. “Syntheses of Cultures and Sensibilities: The Expressions of Moyo Ogundipe.” Life’s Fragile Fictions: The Drawings and Paintings of Moyo Ogundipe, edited by Ohioma I. Pogoson, Ibadan, Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, 2011, pp. 11-18.

“Bird of The Gods: How The Peacock Got His Feathers.” FormFluent, https://formfluent.com/blogs/blog/bird-of-the-gods-how-the-peacock-got-his-feathers?srsltid=AfmBOoocPlJA84zwLeOHB9CRzKnUQr3x6DWu_hqUOovTzgA70dkzd3_E. Accessed 15 Dec 2024.

Drewal, Henry John and John Pemberton III. Yoruba, Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought, New York, Harry N. Abrams Publishers Inc., 1989.

Sytsma, Janine A. “Migratory Mythopoeism: A Critical Examination of Moyo Ogundipe’s Paintings.” African Arts, Vol. 53, No. 1, Spring 2020, pp. 50-65. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/748892. Accessed 7 Oct 2024.

Primary Sources

“Moyo Ogundipe Interview.” YouTube, uploaded by DAMCreativity, 3 Nov 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=937ARTOuwpw. Accessed 28 Oct 2024.

Resources

Afrobeats Wall Text. In exhibition “Arts of Africa” at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Seen on 5 Oct 2024.

Exhibition Text for “Arts of Africa.” In exhibition “Arts of Africa” at Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Seen on 5 Oct 2024.

“Soliloquy: Life’s Fragile Fictions.” Denver Art Museum, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/edu/object/soliloquy-lifes-fragile-fictions. Accessed 7 Oct 2024.

Works Consulted

Scholarly Sources

Enwezor, Okwui. “Contemporary African Art and Globalism.” Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, International Center for Photography, New York, 2006, pp. 20-26.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. “The Idea of National Culture: Decolonizing African Art.” Contemporary African Art. London, Thames and Hudson, 1999, pp. 166-189.

Okediji, Moyo. The Shattered Gourd: Yoruba Forms in Twentieth Century American Art. Seattle and London, University of Washington Press, 2003.

Olusesi, Peace. “Yoruba Art and Aesthetics – 4 Simple Aspects you’ll Appreciate Knowing About.” Discover Yoruba, 23 Dec 2023, https://discoveryoruba.com/2023/12/23/yoruba-art-and-aesthetics-4-simple-aspects/

Primary Sources

Sowole, Tajudeen. “Moyo Ogundipe Returns Home: After 20 years in self-exile, Ogundipe tests the home gallery.” A-Arts: News Review Interview. Aug 2008, republished 19 Nov 2011, https://www.africanartswithtaj.com/2011/11/moyo-ogundipe-returns-home.html

Resources

“Creativity & Identity.” Denver Art Museum, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/edu/lesson/creativity-identity. Accessed 28 Oct 2024.

Originally written December 2024.