Historic house museums are often caught in a struggle between past and present, tasked with merging the historical and the contemporary to share relevant stories that resonate with modern audiences. While many historic house museums strive to incorporate histories beyond the apparent by delving into the labor required (often by enslaved people) to run the home and the roles played by various individuals who lived and worked in the space, these stories are often held captive by the past and disconnected from the present. Interspersing contemporary art objects throughout a historic house offers an opportunity to relate the past to the present more directly by calling to mind new stories and new connections that enhance the historic collection. Using the Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters in Savannah, Georgia as a case study, incorporating the works of Black contemporary artists such as Simone Leigh, Betye Saar, Willie Cole, Kara Walker, and Kerry James Marshall shifts the narratives of objects and spaces within the museum, recontextualizing its significance to a contemporary audience.

With its legal end more than 150 years ago, slavery in the United States can feel like a bygone era, disconnected from our present moment. American society has evolved in many ways, and often strives to make reparations for this horrific national history. But with civil rights movements reaching a volatile apex just seventy years ago, followed by recent political and civil unrest that continues into 2024, systemic oppression is still very present in our contemporary American world, with Black and other persons of color facing unjust, unethical, and often inhumane treatment. Black artists continue making work that speaks to their heritage, struggles, strength, and perseverance, and incorporating these contemporary pieces can help remove some of the glamorization that viewers often associate with period museums – the styles, the colors, the importance of historical materials can often override the daily experience of those living within the home, especially when considering Black slaves. Highlighting an alternative viewpoint that analyzes the lasting impact of these periods on certain communities can share additional context and help audiences understand history more accurately.

Passed down through generations and eventually bequeathed as a museum, the Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters (OTH) already does not shy away from the slave-owning histories of its various owners since its construction in the early 1800s (“Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters”). Tours of the home and the adjacent slave quarters are offered daily, and in 2019 the museum began sharing more detailed histories of the fourteen enslaved people and their arduous daily existence during these docent-guided tours (Mzezewa). OTH’s current consideration of the home’s difficult history and the important conversations that come from sharing these stories with contemporary audiences make it a perfect candidate for expanding these strides toward recontextualization. Incorporating contemporary art pieces within the museum can further illuminate the thorny legacies these difficult histories carry in today’s world while still honoring the hope and strength carried alongside them.

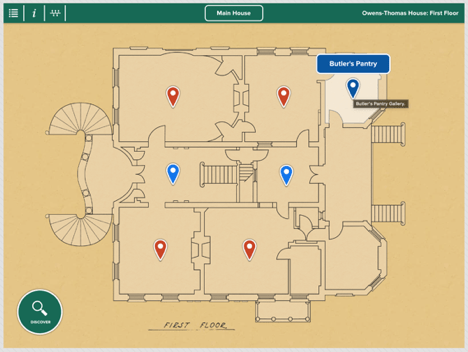

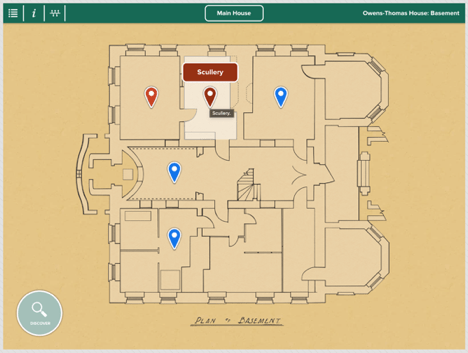

Following the layout of the home, the largest impact of this proposed design comes from placing contemporary art objects in key rooms, blending them in through careful placement so they look to be a natural part of the space. Visitors to OTH enter through the main entrance on the first floor and are greeted by a formal dining room immediately to the left (Fig. 1). This room was used for entertaining guests over dinner, which would have been served by enslaved laborers (“Formal Dining Room”). The traditional 1800s serving vessels such as teapots, pitchers, and glassware are echoed in contemporary artist Simone Leigh’s larger-than-life 2019 sculpture Jug, which morphs the shape of a ceramic jug with a Black woman’s body (Fig. 2). Though eyeless, the sculpted woman’s stare pierces the viewer, as if to challenge their perceptions of her form. Simultaneously, the woman is the jug, and the jug is the woman; there is no distinction between the two shapes, much like slaves during OTH’s time as a family home were solely equated with their role. Placing this contemporary sculpture quietly in the corner of the formal dining room at OTH, amidst the typical historical collection of dining ware expected in a historic house museum, poses a similar challenge to visitors, asking them to contend with the woman’s powerful presence in a room where she is surrounded by her implements of servitude, but was not welcome to dine.

Yet despite its heavy connotations, the sculpture also belies a resilience, beauty, and hope. The jug forms an elegant skirt from which the woman’s delicate torso emerges, and the stance of her upper body is composed and direct, indicating an internal strength as she assumes this external role of servitude. Her hair is styled in a natural afro, often a symbol of pride in contemporary Black culture, honoring her identity as a Black woman. Juxtaposing the sculpture’s contemporary context and visuals with OTH’s historical surroundings speaks to the suffering Black communities have overcome, both as individuals and a collective. The symbolism of the elegant, strong woman emerging from her distressing past serves as an apt analogy for Black culture overcoming barriers and emerging more powerful in the 200 years since the Owen-Thomas House’s construction, and again asks viewers to contemplate the woman’s evolved role in contemporary versus historical society.

Moving from the front left corner of the Owens-Thomas house to the back left corner, visitors enter the Butler’s Pantry, which served as “a storage and staging area of the house” where “food was brought up from the kitchen and plated” (Fig. 3; “Butler’s Pantry”). This space evokes images of breakfasts being assembled by enslaved members of the household, who again would not have been invited to partake in the meals they prepared. Black women in particular often served as caretakers and were ascribed a motherly persona, particularly in the Jim Crow era, when caricatures of Black attributes emerged (Sanyal). One enduring caricature of this time is Aunt Jemima, the eponymous typecast representative adopted by Pearl Milling Company for its line of pancake syrup and mix (McNamee). The woman’s exaggeratedly plump body and smiling face served as the logo for the brand until as recently as 2021, when it was finally abandoned during the national reckoning that followed the 2020 murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police (McNamee).

Artist Betye Saar’s 1972 assemblage Liberation of Aunt Jemima speaks to this tumultuous history, juxtaposing Aunt Jemima as a smiling, caring woman holding a white child with an exaggerated caricature of the woman holding a rifle and a hand grenade that envelops the smiling woman (Fig. 4). The Aunt Jemima syrup logo repeats in the background, adding an uncanny sense of madness. All three women’s faces are frozen mid-smile, and you can almost hear a maniacal laughter coming from their images, lending a threatening, chaotic aura to the piece. Placing Liberation of Aunt Jemima in the Butler’s Pantry at OTH conjures the feelings of suppressed rage lurking beneath the surface as enslaved servants plastered smiles on their faces and prepared food for their oppressors daily. As the assemblage is freestanding, it could be set on a window sill within the room, blending in with other period elements of the serving area. Its size and structure would appear ordinary and natural in the space, but a closer inspection would reveal the deeper truth of the lived experience of Black slaves, both at OTH and after they were freed.

Although Saar’s Liberation of Aunt Jemima visually confronts the viewer, there is also a radical feminism inherent in the piece that evokes strength and power. Rather than succumbing to the constraints and identity applied to her by external forces, Jemima charts her own path, albeit a violent one. She still holds a broom in one hand, but it is paired with the hand grenade, alluding to the persona’s impending destruction. The rifle suggests she is able to defend herself against whatever comes her way; she may appear cheerful and caring, but she is strong and determined, and more than capable of overcoming her restrictions. While the immediate appearance of the piece feels hostile, it is also hopeful – there will come a moment where Jemima, the enslaved workers at OTH, and their descendants will stand on their own volition.

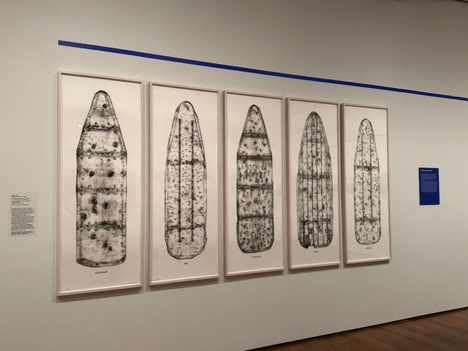

Transitioning downstairs to the basement, visitors encounter the scullery, where laundry and kitchen cleaning duties were performed by enslaved women (Fig. 5; “Scullery”). While ironing boards may not have been commonplace in the nineteenth century, wash bins and other laundry implements are found in this room, foregrounding the arduous physical labor required to complete these tasks. Fitting the theme of this room is Willie Cole’s evocative Five Beauties Rising, a set of five intaglio prints on paper depicting battered, broken, and discarded ironing boards, each with a woman’s name printed in capital letters below the image: Savannah, Dot, Fannie Mae, Queen, and Anna Mae (Fig. 6). By bestowing a human name on an inanimate object, Cole invites the viewer to contemplate whether these images of damaged boards are a memorial to the women who used them, figurative representations of the women themselves, or both. The object’s existing museum label at Harvard Art Museums reveals these images are a “testament to the strength and endurance of generations of Black women” and a “tribute to the manual labor they have performed,” while also leaving room for audiences to impart their own understandings, whether “tombstones, human silhouettes or portraits. . .slave ships,” or something else entirely (Object Label).

By selecting an object as seemingly mundane as an ironing board and imbuing it with human attributes such as a name and blemishes resembling scars, Cole draws a connection between the grueling domestic work done by women past and present. By bestowing the prints with his Black family’s names, Cole further connects these tumultuous images with Black history in particular. These images are simultaneously timeless and laden with history, calling to mind the brutal histories of slavery and colonialism across the globe that still resonate today. Recontextualizing them in OTH asks viewers to reflect on the lasting effects of these abuses and the back-breaking manual labor that takes a toll on the body and soul, as well as its effects on the shared communal psyche that persists into the future. Installing the prints on a blank wall within the scullery, as if they are simply intentional decoration in a space typically unadorned, would heighten this perception by engaging with the unexpected in a discordant manner.

Five Beauties Rising also holds a visual appeal, with its prints also resembling patterned fabric or African masks, as the artist himself once shared (Wall Text). These associations with African culture, which was carried across the Atlantic Ocean as slaves were transported to America, remind visitors that culture is inextricable from identity. Although slaves endured intense suffering, their heritage did not disappear, and these cultural memories may have served as a comfort and strength to many as they continued sharing stories with future generations. By creating objects that are at once an ironing board, battered and broken, and a reimagining of traditional African artifacts, Cole imbued the prints with the hopefulness of steadfast continuity, commending the generations of Black women who have carried their scars while still maintaining their connections to themselves, their heritage, and the promise of the future.

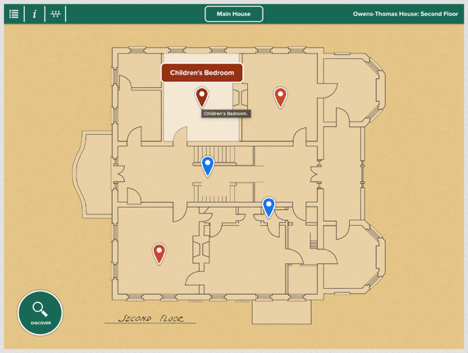

Continuing the Owens-Thomas House tour leads visitors upstairs to the children’s bedroom on the second floor, where a floor blanket is laid on the ground next to a stately four post bed (Fig. 7). This blanket was reserved for the children’s nursemaid Emma Katin, who was likely forced to forfeit a relationship with her own daughter in favor of raising her owner’s white children (“Children’s Bedroom”). The opulence of the bed juxtaposed with the stark discomfort of the floor blanket set aside for Emma visually highlights the inequality experienced by Black women during slavery. Enslaved women were expected to care for white children as if they were their own, but were not afforded the comforts of an actual bed to rest from these duties. Additionally, despite forming a close connection with these children, the children were raised to believe they were inherently better than Black people, perpetuating this inequality.

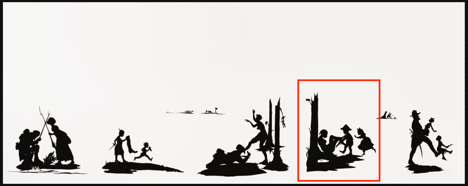

Incorporating a segment of Kara Walker’s 1995 silhouette The Battle of Atlanta: Being the Narrative of a Negress in the Flames of Desire—A Reconstruction in the children’s bedroom emphasizes this disconnect between white children and their Black nursemaid. The silhouette depicts two children aiming a sword at the uterus of a Black woman, who is tied to a tree (Fig. 8). Walker’s work seems decorative and unassuming at first, with shapes that almost appear joyful and playful. Without further examination, the pieces appear almost idyllic, but their horrifying content focusing on the brutality of slavery’s everyday moments is sobering, especially in silhouettes including children inflicting violence. Author Erica Cardwell explains “it was confusing that the violence had been difficult to discern at first. The truth was confined to the impression of the silhouettes” (Cardwell). Placing such a vicious silhouette in a child’s bedroom, which could be presumed as a safe space full of imagination and comfort, startles visitors’ assumptions and confronts them with a reality of slavery: that inequality and hatred was passed along through generations, and lingered long after slavery was abolished. There is little hope in this interpretation, but it serves as a somber truth that children could be complacent in the institution of slavery as well, even with a motherly nursemaid sleeping close by.

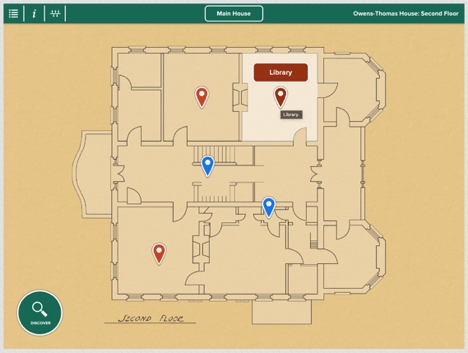

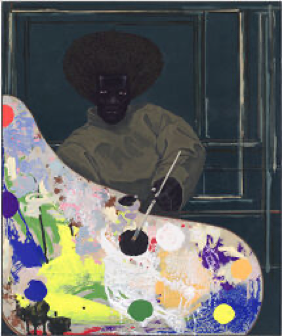

Rounding out this tour of OTH is the library, where the white patriarchs of the household likely read and discussed new knowledge and ideas of the time (Fig. 9). The room is adorned with painted portraits of white men and women, memorializing their contributions to America’s colonial history and innovation in the nineteenth century (“Library”). Yet missing from this room is the contributions of Black men and women to America’s growth and creativity; without Black labor, ingenuity, and perseverance, the new country would not have thrived. Replacing an existing portrait of a white man with Kerry James Marshall’s untitled 2008 work reminds the visitor that Black brilliance was present, regardless of their status as slaves, and it continues to flourish today (Fig. 10). Marshall’s work features a Black artist, again with a traditional afro honoring his heritage (echoing Simone Leigh’s Jug), staring pointedly at the viewer while holding a paint palette extended toward them, as if to engage them in a question or a challenge. The expression on the artist’s face serves as an apt ending to the tour, as it can be interpreted as saying, “yes, we were here too, despite this house’s outward evidence to the contrary,” and, “now that you know we were actively here, how does that reshape your perception of colonial and slave histories and knowledge-making?”

Marshall’s work can also be understood in a future-focused manner, as the artist’s paintbrush on the palette is dipped in the same deep black color with which his skin is painted. This symbolizes that Black communities will continue creating their own futures, painting their visions and achieving their goals, and exceeding all limitations imposed on them by external forces. It can also invite viewers to pick up their own metaphorical paintbrushes and help rewrite history to include these excluded narratives, painting a clearer picture of how slavery truly unfolded and how its effects linger systemically today. In 2024 when schools across the United States are limiting what histories are taught and how, this latter call to action feels more important than ever. And so incorporating contemporary art to help reframe historical collections feels more important than ever too.

As with any exhibition, it is difficult to expect that all audiences will implicitly understand the intention behind this disruption of an existing historical collection, so supplementary materials should be provided to visitors upon embarking on the tour of the historic home. Drawing inspiration from Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society in 1990, one helpful approach is sharing a series of questions that invite the viewer to consider what the objects are, where they are placed, whose stories they tell, and how they shift the viewer’s understanding of what else they observe in the house. While OTH’s tours do include the slave quarters as well, placing these contemporary works by Black artists within that space feels more expected, and may do less to reframe the role of Black slave labor in audiences’ minds. However, the conversations and interpretations revealed during the tour of the primary house will influence the visitor’s perception of the slave quarters as they tour that space, adding additional context to lived history.

Also important is limiting the conceptual separation between the historical collection and the contemporary pieces infused throughout the house. By creating a distinction between the two, the juxtaposition runs the risk of being interpreted as disparate from the existing content of the house, perhaps as an overlay rather than an amalgamation. Designing the work of these Black artists directly into the space, as if they were always intended to be there, supports the narrative that past and present are often more intertwined than we think, and that it is crucial to consider multiple viewpoints and perspectives to frame both the past and present. The impact of these images and the labor, trauma, and strength they carry is a stark reminder that real humans used the objects we associate with the past in these historical homes, even if their names are not directly recorded or remembered or shared as part of the object’s history.

Introducing contemporary art into historic house museums can revitalize and recontextualize the narratives the objects within the houses’ collections tell by offering new, updated perspectives that artistically connect to historical experiences. Juxtaposing art by living Black artists with seemingly static objects used by enslaved Black communities emphasizes that the labor required to use these objects and the suffering and abuse endured during their use are still deeply felt in the present day, and certain issues from the past still persist into today’s world. By challenging viewers’ perceptions and understandings, historic museums can engage more deeply with contemporary audiences and share more relevant stories that invite visitors to act to help close the gaps between perceived history and lived history. This blend of past and present also prompts visitors to question their modern assumptions of equality, and how we can still improve on the past in our present day. In a country plagued by political discord and civil unrest, this endeavor of learning stronger lessons from the past feels crucial, and essential to building a more equitable future.

Appendix

Fig. 1. GPB Education. “Owens-Thomas House: First Floor.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/04_MainHouse_FirstFloor/index.html#FirstFloor. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

Fig 2. Simone Leigh. Jug. 2019. Bronze. In exhibition “Simone Leigh” at ICA Boston, Boston, MA. Seen on 6 Apr. 2023.

Fig. 3. GPB Education. “Owens-Thomas House: First Floor.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/04_MainHouse_FirstFloor/index.html#FirstFloor. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

Fig 4. Betye Saar. Liberation of Aunt Jemima. 1972. Smarthistory: The Center for Public Art History. https://smarthistory.org/betye-saar-liberation-aunt-jemima/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.

Fig. 5. GPB Education. “Owens-Thomas House: Basement.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/03_MainHouse_BasementFloor/index.html#Basement. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

Fig 6. Willie Cole. Five Beauties Rising. 2012. Intaglio and relief on paper. In exhibition “Future Minded: New Works in the Collection” at Harvard Art Museums, Boston, MA. Seen on 2 Mar. 2024.

Fig. 7. GPB Education. “Owens-Thomas House: Second Floor.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/05_MainHouse_SecondFloor/index.html#SecondFloor. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Fig 8. Kara Walker. The Battle of Atlanta: Being the Narrative of a Negress in the Flames of Desire – A Reconstruction. 1995. 17 paper silhouettes. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA. https://hammer.ucla.edu/exhibitions/2023/kara-walker-selections-hammer-contemporary-collection. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Fig. 9. GPB Education. “Owens-Thomas House: Second Floor.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/05_MainHouse_SecondFloor/index.html#SecondFloor. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Fig 10. Kerry James Marshall. Untitled. 2008. Acrylic on PVC Panel. Harvard Art Museums, Boston, MA. https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/328488. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Works Cited

Cardwell, Erica. “Kara Walker and the Black Imagination.” The Believer, 13 Dec. 2017, https://www.thebeliever.net/logger/kara-walker-and-the-black-imagination/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.

GPB Education. “Butler’s Pantry.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/04_MainHouse_FirstFloor/galleries/firstfloor_diagram/gallery_1/index.html#GalleryPhoto1. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

GPB Education. “Children’s Bedroom.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/05_MainHouse_SecondFloor/index.html#ChildrenBedroom. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

GPB Education. “Formal Dining Room.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/04_MainHouse_FirstFloor/index.html#FirstFloor. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

GPB Education. “Library.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/05_MainHouse_SecondFloor/index.html#Library. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

GPB Education. “Scullery.” Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://edu.gpb.org/FINAL/VFTs/HTML/owens-thomas-house-ga/03_MainHouse_BasementFloor/index.html#Scullery. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

McNamee, Gregory Lewis. “Aunt Jemima (Pearl Milling Company).” Britannica, 30 Jan. 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aunt-Jemima-Pearl-Milling-Company. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.

Mzezewa, Tariro. “Enslaved People Lived Here. These Museums Want You to Know.” New York Times, 26 Jun. 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/26/travel/house-tours-charleston-savannah.html. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.

Object Label for Five Beauties Rising, 2012 by Willie Cole. In exhibition “Future Minded: New Works in the Collection” at Harvard Art Museums, Boston, MA. Seen on 2 Mar. 2024.

“Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters.” Telfair Museums. https://www.telfair.org/visit/owens-thomas/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.

Sanyal, Sunanda K. “Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima.” Smarthistory: The Center for Public Art History. https://smarthistory.org/betye-saar-liberation-aunt-jemima/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.

Wall Text, Willie Cole quote. In exhibition “Future Minded: New Works in the Collection” at Harvard Art Museums, Boston, MA. Seen on 2 Mar. 2024.

Originally written March 2024.