Although initially controversial, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial humanizes the remembrance of war. The memorial’s visual narrative invites visitors to connect with their personal experience as they view their reflection among the names of the dead etched into the wall’s surface. This powerful act stirs myriad emotions. Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Facing It” helps analyze the memorial’s impact and significance, highlighting how it can trigger and trap, but also heal. The minimalism of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial creates space for all of these perspectives, and Komunyakaa’s experience reminds us that the true memorials of war are our memories.

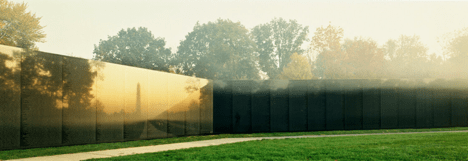

War memorials are multifunctional: they serve as representations of honor and loss, tributes to battles bravely fought, and a setting to remember experiences of war. Over the last 40 years, the aesthetic standard for memorials has become apolitical and unassuming, allowing us to quietly contemplate the honored war without any particular expectations. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC set that standard in the early 1980s, offering a reserved yet powerful commemoration model. From its inception, however, the memorial’s minimalist and politically neutral design proved controversial. Many veterans argued it deviated too far from previous war memorials and thus did not appropriately honor the glory of battle and dying in war. Others deemed it an elegant tribute to this catastrophic period of American history. Delving into the memorial’s visual narrative, using Yusef Komunyakaa’s 1988 poem “Facing It” as a lens, reveals how it powerfully humanizes the remembrance of war by reflecting our individual experiences back to us, no matter our perceptions of war. The memorial invites each visitor to assess what their experience of the memorial means to them, reminding us that it is truly our memories that serve as the enduring memorials of war.

The historical controversy surrounding the memorial’s creation foregrounds the power held by its individualization. When Vietnam veteran Jan Scruggs launched a design competition for the memorial in 1979, he “[did] not seek to make any statement about the correctness of the war,” but aimed to create a memorial that “[transcended] the tragedy” of it (Wolfson). As Wolfson details, the competition’s jurors unanimously selected artist Maya Lin’s design for its dissimilarity from traditional memorials, unique horizontal stature, and polished black surface adorned only with the names of the dead etched into the granite. Wolfson explains that although the design appeared apolitical, critics of the monument immediately waged a cultural war upon it, arguing its stark deviation from tradition proved it was an anti-war memorial that did not celebrate Vietnam soldiers as heroes. Veteran Tom Carhart notably critiqued it as a “black trench that [scarred] the Mall” with its “[b]lack walls, the universal color of shame and sorrow and degradation” (Wolfson). The National Review, as quoted in “The ‘Black Gash of Shame,’” claimed the memorial made the deaths of the soldiers “individual deaths, not deaths in a cause; they might as well have been traffic accidents.”

But it is this very individualization of death that makes the Vietnam Veterans Memorial so uniquely impactful. Each viewer’s experience reflects their perceptions and connections to the war, imbuing the memorial with myriad significance. Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Facing It” powerfully details his visit to the memorial as a veteran of the war. He is overwhelmed with emotion as he stands before the names on the wall. Light plays off the mirrored surface of the memorial throughout the poem, blurring time and space and transporting him back into his experiences of the war. The memorial’s polished surface becomes even more poignant as Komunyakaa, a black soldier, watches his “black face [fade] / hiding inside the black granite. . .I’m stone. I’m flesh” (Komunyakaa 359). His face hiding in the memorial suggests the memories of the war hide within him as he hardens himself to the world, transforming into a human manifestation of the memorial’s black granite. As he visits the memorial, he inhabits both the present moment and his memories, and it is so powerful that he slips “inside / the Vietnam Veterans Memorial / again,” with only “the light / to make a difference” in distinguishing past from present (359). The etched names of the dead on the wall appear as “letters like smoke,” as not quite tangible, just like his memories of the war (359). The memorial’s mirrored surface reflects Komunyakaa’s personal experiences of the war, and this simple action emphasizes how individual each visitor’s experience can be.

In 1980, Lin designed the memorial to be “human, and focused on the individual experience” (Lin). And it is exceedingly personal – rather than selecting a matte or rough finish to absorb and contain the emotions of its viewers, Lin chose a mirrored black surface that invites you in and reflects the pain and loss of war by transposing the names of the dead on the faces of the living. This passive yet powerful act forces the visitor to examine their perceptions of war, in Vietnam and elsewhere. For some, seeing their faces among the names of their lost relatives is a reminder that their loved ones live on in them. Others feel implicated in the loss of the soldiers, wishing they could have done more to prevent it, or imagine if their names were on the wall instead. Still others feel fierce pride for those who fought bravely for our country and sacrificed their lives to protect it. Each individual’s experience of the memorial is valid, accentuating that our memories serve as the best remembrance of war and tribute to our lost soldiers’ lives.

This reflection of personal experience at the wall can also trigger and trap a visitor, as “Facing It” describes. As Komunyakaa’s memory transcends time, he becomes a window to his lived experience of the war. His “clouded reflection eyes [him] / like a bird of prey,” suggesting he is wary even against himself as he remembers the war, or that this hypervigilance stayed with him even as the war ended (Komunyakaa 359). Locating a familiar name on the wall triggers Komunyakaa to “see the booby trap’s white flash” that killed the man, marking a turning point in the poem – the soldier within Komunyakaa takes over, and he conflates the benign actions of the crowd with wartime attacks (359). The stoic black memorial transforms into a battleground for him (and him alone) as the reflection of “[a] plane in the sky” transforms into a bomber, and a man “[loses] his right arm” in a trick of the light on the memorial’s surface (360). Komunyakaa is at the mercy of the memorial – the tension he feels as he and his memories are trapped in the black granite convey a palpable sense of fear and stress.

As Komunyakaa relives the trauma of the past, we also sense his profound grief in the present. As the poem opens, he swears to himself he “said [he] wouldn’t / dammit: No tears” (359). He still grapples with the effects of the war on his psyche over a decade later, and the memorial provides space for him to process that grief as it flows out of him. We feel Komunyakaa’s emptiness as he scans the names on the wall, “half-expecting to find / [his] own,” and understand that he has felt half-dead since his return from the war, regardless of whether his name is etched in the stone (359). Lin was aware of the emotional pain the war wrought, and her vision of “cutting into the earth and polishing its open sides, like a geode” serves as a symbol of healing – if we can polish a gash in the earth and reflect on our grief as we do, perhaps in time (or place) we can also heal the grief of the “black gash of shame” created by the war itself (Lin; Wolfson).

The visual narrative of submerging the memorial below grade also humanizes our grief by recalling the way the dead are laid to rest. War memorials historically rose toward the heavens, exalting soldiers and glorifying death (Wolfson). Lin’s decision to instead orient the Vietnam Veterans Memorial horizontally reminds us that our soldiers and veterans are human above all else, and here they are remembered as such. From a soldier’s perspective, the horizontal orientation also resembles soldiers waiting out a siege in trenches, or bodies strewn across a battlefield after a fight. Lin also imbues this darker interpretation with hope; the aerial view of the memorial highlights the contrast between the polished black granite and the natural landscaping around it, conveying that even the deepest gashes can be healed.

Detractors of the memorial argued that thrusting veterans into reliving the war at a memorial created to remember their sacrifices did not honor them with dignity. Veterans who opposed its design viewed it as another affront to Vietnam soldiers who had already endured so much vitriol from the American public for their role in such a controversial war. They maintained that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial should follow the tradition of Neoclassical war memorials whose visual narratives actively glorified the cause and venerated the soldiers (Wolfson). But glorification of war is not always accurate, especially when it comes to a war as harrowing as the Vietnam War. Yet it is written into human history as the primary way to commemorate these events. Creating a memorial that did not align with that narrative forced society to examine their true feelings and biases toward the war, alongside their treatment of returning Vietnam veterans. Critiquing the memorial was an attempt to avoid that discomfort by deflecting and reframing America’s involvement in the war’s devastation.

“Facing It” alludes to these efforts to reframe the catastrophe of the Vietnam War. As Komunyakaa relives his memories of the war as he stands before the wall, he sees “a [woman] trying to erase names” though she is only “brushing a boy’s hair” (Komunyakaa 360). The erasing of names hints at America’s attempts to distance itself from its role in the war (and the home front response to returning soldiers). As Wolfson explains, many Americans escaped their discomfort by separating from the horror of the war, “[removing it], like a tumor, from the body of the nation and [assigning it] to another geographical location: Vietnam.” This desire to rewrite the Vietnam War pulled from collective memory that had warped over time, “[healing] over the wounds that had refused to close for ten years with a balm of nostalgia” and “[transforming] guilt and doubt into duty and pride” (Clark 49). But Komunyakaa’s poem shows that the truth of the war lives on, at least in the subconscious of the veterans who survived it. As long as their stories are passed down, the true memorials of the war continue on.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial allows these perspectives to coexist – it reminds us of America’s failures, and it quietly holds the suffering of veterans, and it reflects the hope of healing. It invites the public to engage with a tragic moment in history in a real, unfiltered, and unpolished way – despite juxtaposing those strong emotions with a pristine surface that would seem to indicate otherwise. The memorial holds a mirror to what society becomes during times of war, while neither condemning nor condoning it. Rather, it lets the individuals within the society determine what it means for themselves. We are all memorials of the war. It is written into collective history through lived experiences and shared stories. We carry this collective history together but also alone – we are the memorial, and the memorial is us.

Appendix

Lin, “Vietnam Veterans Memorial.”

Lin, “Vietnam Veterans Memorial.”

Lin, “Vietnam Veterans Memorial.”

Works Cited

Clark, Michael. “Remembering Vietnam.” Cultural Critique, No. 3, American Representations of Vietnam (Spring 1986), pp. 46-78, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1354165. Accessed 7 May 2022.

Komunyakaa, Yusef. “Facing It.” The New Oxford Book of War Poetry, edited by John Stallworthy, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 359-360.

Lin, Maya. “Vietnam Veterans Memorial.” MAYA LIN STUDIO, https://www.mayalinstudio.com/memory-works/vietnam-veterans-memorial. Accessed 27 April 2022.

Wolfson, Elizabeth. “The ‘Black Gash of Shame’ – Revisiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Controversy.” Art21 Magazine, 15 March 2017, http://magazine.art21.org/2017/03/15/the-black-gash-of-shame-revisiting-the-vietnam-veterans-memorial-controversy/#.Ykn2KZPMJpQ. Accessed 3 April 2022.

Originally written May 2022.